Breaking the Bottleneck in Maternal Mental Health

A Scalable Solution to Suicide

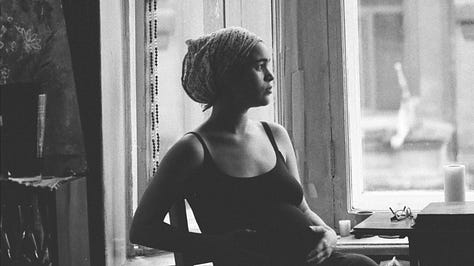

Suicide ranks among the leading causes of maternal death during pregnancy and postpartum. That sentence carries weight that bears repeating, slowly. We lose mothers to despair when they should be receiving care, celebration, and the protective web of community support. The gap between what new parents need and what our systems deliver has widened into a chasm.

A major clinical trial called SUMMIT recently quantified this crisis with uncomfortable precision. Among 1,117 participants, nearly one in four (23.6%) reported suicidal thoughts during pregnancy or the postpartum period. Picture a room of expecting parents at a prenatal class. Now picture six of them silently carrying thoughts of ending their lives while learning breathing techniques and discussing nursery colors.

Yet this same study revealed something genuinely hopeful. A form of psychotherapy called Behavioral Activation produced remarkable results in reducing suicidal ideation. The findings matter because they work, certainly. But they matter even more because of who can deliver this therapy and how.

Behavioral Activation reduced suicidal thoughts with measurable, progressive force. Each additional therapy session decreased the odds of a patient endorsing suicidal ideation by 25%. Think of that as a ratchet mechanism, each session clicking the risk downward with reliable consistency.

The trajectory continued past the treatment window itself. Three months after therapy concluded, the odds of endorsing suicidal ideation had dropped by 80% compared with measurements taken during active treatment. A relatively brief intervention (just six to eight sessions) created protection that extended and deepened over time. The therapy appears to set a different course in motion rather than simply suppressing symptoms while active.

This matters because postpartum life moves fast. The fourth trimester arrives with relentless demands and compressed timelines. Parents often struggle to attend even a handful of appointments between feeding schedules, sleep deprivation, and the logistics of moving an infant through the world. An intervention that creates lasting change within eight sessions fits the reality of early parenthood rather than demanding that reality bend to accommodate lengthy treatment.

Behavioral Activation works by increasing what researchers call “values-consistent living” while building awareness of ineffective behavioral patterns. In plain language: the therapy helps people identify what truly matters to them, then guides them toward small, concrete actions aligned with those values. When your world has contracted to a series of overwhelming tasks performed in isolation, this approach opens a path back to meaning and connection. You become what you attend to. The therapy redirects attention toward chosen life rather than away from unbearable circumstances.

Specialization Matters Less Than We Assumed

Here the research challenged conventional wisdom in a way that reshapes possibilities. The therapy proved equally effective whether delivered by mental health specialists (e.g., psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers) or by non-specialists including registered nurses, midwives, and doulas.

Read that again. The outcomes showed no significant difference based on provider type.

This finding upends assumptions about who can offer life-saving mental health care. We tend to imagine that effective therapy requires years of specialized training in psychotherapy techniques, that the therapeutic relationship depends on credentials and clinical expertise accumulated over decades. Sometimes that holds true. For Behavioral Activation targeting perinatal suicidal ideation, it simply does not.

The implications ripple outward. Mental health specialist shortages create bottlenecks everywhere, but especially in rural areas, lower-income communities, and regions with insufficient infrastructure. Wait times stretch for months. Parents in crisis encounter closed doors and full practices. Meanwhile, trusted care providers who already walk alongside these same parents through pregnancy and birth often feel helpless when psychological symptoms emerge, trained to recognize warning signs but required to refer elsewhere for treatment.

Task-sharing (the model where non-specialists deliver evidence-based interventions following structured protocols) dissolves this bottleneck. A midwife who has earned trust over months of prenatal visits can now offer the therapy itself rather than handing off care to a stranger. A doula supporting a family through the postpartum transition can address suicidal thoughts directly rather than only providing emotional presence while waiting for outside help to arrive. The pool of potential providers expands dramatically while continuity of care improves.

This approach requires training, certainly. Non-specialists need structured protocols, supervision, and clear guidelines. But the research demonstrates that specialized mental health credentials prove unnecessary for delivering this particular intervention effectively. The therapy works because the method works, used with care and fidelity by providers who already possess relationship skills, empathy, and commitment to maternal wellbeing.

The study revealed one more critical finding.

Therapy delivered via telemedicine produced results identical to in-person treatment. No difference in effectiveness based on delivery method.

Consider what this means for a new mother living forty miles from the nearest mental health provider, managing postpartum depression while caring for a newborn and possibly other children. Transportation barriers alone can make treatment impossible. Arranging childcare multiplies the difficulty. For rural parents, geographic isolation compounds emotional isolation in ways that intensify risk.

Telemedicine removes these barriers entirely. A parent can receive evidence-based, life-saving therapy from home during a nap window or after older children board the school bus. The midwife or nurse who already knows their story can deliver sessions via video call, maintaining continuity rather than requiring transfer to an unfamiliar provider in an unfamiliar office. Help arrives where people actually live rather than demanding they travel to where help traditionally resides.

This flexibility matters beyond logistics. Postpartum life often involves physical recovery from birth, potential mobility limitations, and the simple reality that leaving home with an infant requires elaborate preparation that can feel overwhelming when depression has already drained your capacity for planning. Therapy that adapts to these constraints rather than adding to them removes one more obstacle between crisis and care.

The combination of task-sharing and telemedicine creates something genuinely new: a model where a trusted midwife in another state can support a struggling parent through video sessions, where a rural health nurse can offer specialized mental health intervention without referring out, where care becomes portable and scalable in ways previously unimaginable. The infrastructure exists. We carry it in our pockets. This research validates using it for one of parenthood’s most urgent needs.

What This Means for Care Going Forward

The SUMMIT trial provides clear evidence for a specific, actionable path. Behavioral Activation works. Six to eight sessions create meaningful, lasting reduction in suicidal ideation. Non-specialists can deliver it effectively. Telemedicine removes geographic and logistical barriers. These findings together suggest something larger than an effective intervention. They suggest a new standard of care within reach.

Implementation will require intention and resources. Training programs need development and funding. Supervision structures must support non-specialist providers. Healthcare systems need to integrate this approach into standard perinatal care pathways rather than treating mental health as a separate silo requiring referral elsewhere. Insurance coverage and reimbursement models must recognize and support task-sharing approaches. None of this happens automatically simply because the evidence exists.

Yet the evidence does exist now, published and peer-reviewed and clear in its implications. We possess a proven tool for addressing one of maternal health’s most devastating outcomes. The question shifts from “what works?” to “will we implement what works?”

Behavioral Activation offers something rare in mental health research: a therapy that reduces risk substantially, operates efficiently within abbreviated timeframes, scales through expanded provider types, and reaches isolated populations through technology. Each element alone would merit attention. Together they form a comprehensive solution to a crisis that has persisted partly because solutions seemed either ineffective, impractical, or inaccessible.

Hard truths remain. Some parents will still require more intensive intervention. Some cases involve complexity beyond what brief therapy addresses. Some suicidal crises demand immediate psychiatric evaluation and safety planning that Behavioral Activation alone cannot provide. This therapy represents a powerful tool within a broader system of care, valuable and evidence-based but operating alongside other necessary interventions rather than replacing them entirely.

Still, if we could reduce suicidal ideation among pregnant and postpartum individuals by 80% through a brief, scalable therapy deliverable by multiple types of trained providers via telemedicine, that would transform outcomes for thousands of families. The research shows we can. The question becomes whether we will.

Start by asking what this means in your own community. Who provides perinatal care? Where do mental health gaps create the most danger? What would it take to train trusted midwives, nurses, and doulas to deliver Behavioral Activation? How could telemedicine infrastructure support rather than replace existing relationships? These questions have answers now. The evidence points toward action. Choose one step. Systems change through small, consistent moves aligned with clear purpose.

For parents drowning in suicidal despair, access to evidence-based care delivered by trusted providers represents freedom from barriers that have kept help distant and abstract. For healthcare systems, taking responsibility for implementing proven interventions represents freedom from accepting preventable maternal deaths as inevitable. The path exists. Let’s walk it.